(LONG READ) Experience from practice and information from literature made me understand it is difficult to answer the question above for both students and professionals. Why? Because multiple aspects come into play when designing and selecting the proper delivery system for a construction project, the traditional design-bid-build (DBB) system or an integrated system (DB). Or, maybe one of the many variants.

I had trouble finding a to-the-point article or paper to answer the question. Winch, our main textbook hides arguments related to the outsourcing challenge in different chapters. Several papers address related issues and components like factors of project success, project definition, project failure, delay and budget overruns, the principal-agent problem, risk allocation, etc.

Why is it important to discuss this specific topic early in the course? Because the choice of a matching delivery model is essential for your overall strategy. Besides, the choice needs to be made early in the process to be able to prepare the proper procurement documents.

Let us first see what we can find in the literature.

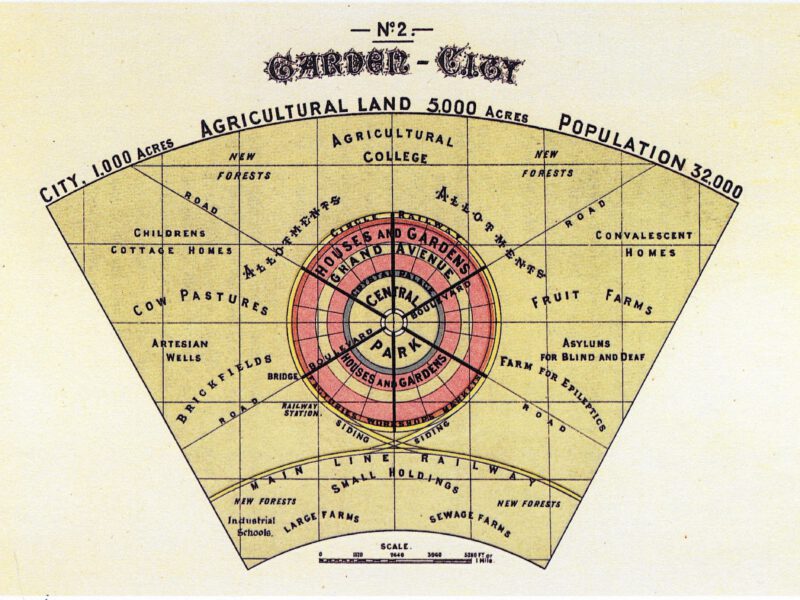

The project delivery method is the process of outsourcing the design and construction of any facility, the method for clients to deliver and finance constructed facilities (Miller, 1999). In the construction industry, different kinds of project delivery methods are available. We have what we call the traditional way of first designing and then constructing a facility according to the completed detailed design in the building specification. Also called the Design-Bid-Build (DBB) method. (Hale et all, 2012). And we have what we call the Design and Build method (DB). An outsourcing method, where one legal entity or consortium is contractually responsible for both the design and the construction of a project. (Songer et all, 1996). We use the term, integrated contracts often.

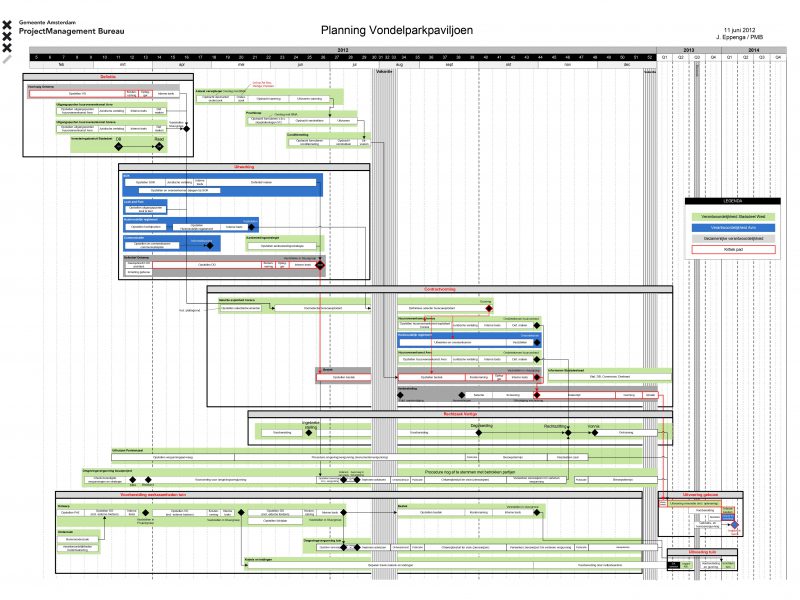

In DBB the client first chooses, often through tendering, a team of designers to design the facility and thereafter compose the building specifications. The client needs a brief to select and award designers. Another name for a Brief is the program of requirements. The building specifications are needed to tender for a contractor but are also needed for the execution and delivery of the facility. Awarding the job to a contractor is often at the lowest price but can be combined with more qualitative criteria. During the construction, the design team controls the contractor on the quality of delivery on behalf of the client. DBB is often called the traditional model. Typical of the traditional model is that there are two tender processes in the timeline of the project and that the design (team) is, from an organizational point of view separated from the execution done by the contractor.

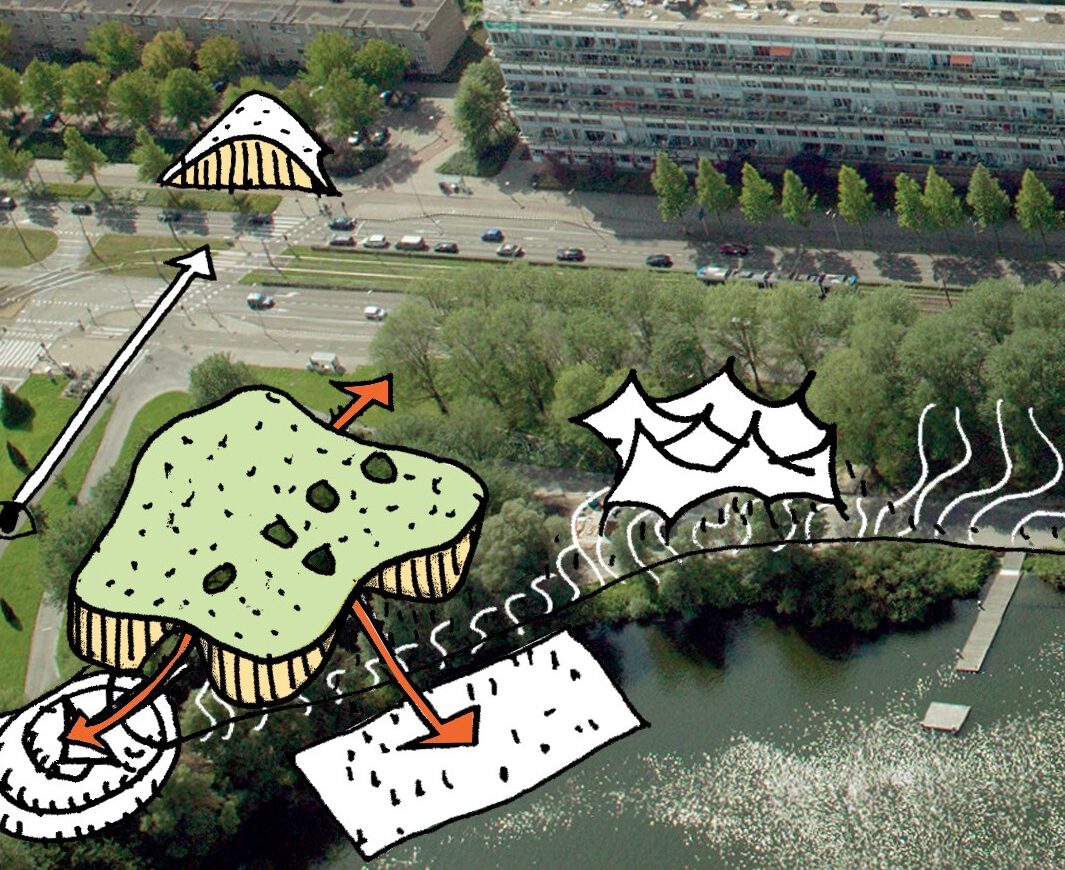

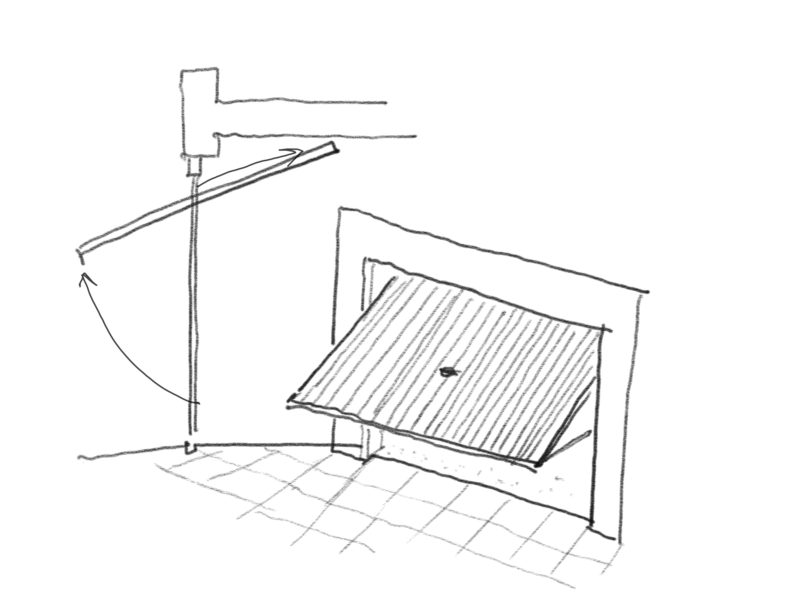

In the integrated model, the client chooses a consortium often through tendering to take care of everything related to design, construction, and delivery. You can see it as a complete package of work. For this model, the client needs to be able to define the project in a complete way early in the process, before designs are made. He/she needs to be confident that he/she will get, maybe years later, what is wanted, what is written down, or what is needed without having a design. The consortium takes over the responsibility for the design, the building specifications, the detailed engineering, the permits, subcontracting, execution, etc., and delivery. The typical document needed to tender a DB consortium is different from the BRIEF and is called output or performance specifications, sometimes combined with an architectural ambition document.

Where do you start to analyze the problem of choosing the best model? Let us start with the position of the client and key characteristic factors affecting Project delivery systems decision-making. We find this in the paper of Liu et al (2014): (1) responsibility, (2) the owner’s willingness to be involved, (3) the owner’s in-house technical capability, (4) risk allocation, and (5) the owner’s willingness to control over design. This is an interesting list because all characteristics point to the client.

Let us look at the client.

Is your client a public client or a private client? Is it a professional client or someone who is a one-time commissioner? This could hugely influence the project-delivery choice.

Before I describe different clients let us look at the nature of the building industry related to product development. If you want to buy a new car, you can go to the shop that sells the brand you like. The thing is ready to go. Most cars are designed, constructed, and sold by one company or one brand. No sensible person would come up with the idea to design a car himself and then find someone or a whole supply chain to make it. This would be expensive and very difficult to accomplish! The car industry is extremely fragmented, having long, often international, and multiple supply chains with hundreds of advisors, suppliers, transporters, consultants, buyers and sellers, designers, etc. And remember that it is not only about the components that make the car but also about the equipment and robots in the assembly lines. Industry on its own.

In the building industry, we do not have brands selling off-shell finished buildings, roads, or bridges. Except for some countries where they make prefabricated houses in factories, loaded on trucks, and assembled on site. The building industry, like the car industry, is an intertwined supply chain with all its stakeholders connected through agreements, contracts, quality control, international and national rules, laws and regulations, quality testing, insurance, liability, warrants, etc. Clients need to understand that they will be part of this complex world when they (re)develop a building. And that everything is connected through contracts and of course payments.

A private, professional client, for instance, a project developer knows the market well. He/she understands the supply chain and knows the possible future buyers. He/she is – for instance – specialized in apartment buildings or office buildings. Therefore, he/she is able to develop and is sufficiently experienced to oversee the work and the risks. Steering the project is their profession. Outsourcing is normal for these professionals and they do the management themselves. Winch refers to this as an in-house capability. (Winch, 2010, p.101).

You could also state that if the project is not that complex or difficult to define, or if the project is a repeat project (an office building) and the client has the experience why not outsource it all and allocate the risks to the contractor and secure profit early in the process? In practice, you see developers do both: in-house project management and outsourcing to the market. Remember that even if you steer a project in-house you need to select and hire many agents.

Public clients, especially the bigger municipalities and governments are also professional clients. They often have departments of professionals developing public buildings and maintaining them. The variety of municipal buildings is often large, from schools to concert halls, from city yards to community centers, theatres and sports facilities, parks, roads, and public spaces. If the capability and capacity are available, public clients will manage the projects. Often in a traditional (DBB) way. Next to that, we see many governments, commissioning projects in an integrated way. Then they challenge the market to come up with solutions for a task. They have their arguments to outsource it all and sometimes it is only for political reasons. (Zeegers, 2014).

Housing corporations are also professional organizations in the building industry. Dutch social housing corporations have maintenance departments and often development departments too. In the past, most housing projects in the Netherlands were organized in a traditional way. Nowadays social housing corporations use a variety of delivery systems to construct new buildings, and also design and build and bouwteam.

It is remarkable that Liu, in defining the five factors mentioned above, uses the word willingness for the client to be involved and to control. It suggests that clients want to be involved, during the whole process and especially during design. For me, there are several reasons why clients are willing to be involved or not: project definition, trust, control, and policy.

Many clients are not able to define the output of a project at the start completely. Most clients are not able to imagine a building without a design. Then maybe clients are forced to choose for Design Bid Build. During design, they then have the freedom to think and discuss further and develop their brief. Together with their architect and the (technical) design team, they come to solutions, discuss design variables, play with cheaper or more expensive proposals, allocate budget for a specific goal, weigh one option to the other, rethink requirements, or maybe come to the conclusion, that the program of requirements was not that good after all. We know from literature and practice that the dialogue between the client and the design team is often needed to rethink requirements, create better solutions, or improve design proposals. Design discussions are needed to solve the information asymmetry between clients and designers, unveil hidden solutions and disclose private knowledge. (Winch, 2010, p.229). In the above-mentioned research Liu also mentions the ability to state clear end-user requirements as a factor affecting the choice of a delivery method. But it is not a priority in the paper, remarkable to me.

There is a second reason why clients are willing to be involved and that is trust or distrust. We will read and discuss a lot about trust and trust-related issues during the course. Outsourcing work comes with a typical problem: the principal-agent problem. Are you sure, you select the best agents for the job? (Adverse selection). Will these agents always act on your behalf, and be trustworthy the whole time they work for you? (Moral hazard). Winch states that architects sometimes appear to care more about their own reputation than meeting the client’s needs (2010, p.75). What about contractors sending in an abundance of change orders to the client or delivering inferior quality? As explained above the building industry is an outsourcing industry and clients will need to close multiple contracts during the process. All tasks in contracts need to be scheduled and controlled, payments need made and delivered stuff checked. If quality is not met or agents deliver over time the process will be hampered, payments postponed or penalties imposed. This all needs to be managed and if problems occur, they need to be solved. Outsourcing and contracting come with a lot of work, obligations, and risks to the client. He/she needs to have knowledge about the typical contractual provisions and laws in the building industry. If a client chooses a DBB contract because he wants to be involved in the design process the outsourcing task is his/her obligation and more comprehensive related to the DB model.

The question is of course, will a DB model free the client from the principal-agent problem and free the client from outsourcing obligations? I think not. In her paper about monitoring the performance of DB contracts, Zeegers (2013) addresses the system of clients’ obligations on control, quality and performance checks, auditing, payments and deductions on payments, etc. She even explains that sometimes the control function is outsourced as well. I find her conclusion specifically interesting: “The building industry is not fully ready for these new types of work (integrated contracts) because contractors are still organized in a traditional way. Organizations are more focused on troubleshooting than on prevention by proactive work. (Zeegers 2013). So control is needed!

I would like to discuss one last consideration influencing the choice of a delivery model: the client’s policy. Since the beginning of the century, the Dutch government increasingly uses DB contracts for their projects. This is driven by the policy of the Dutch Government and following the slogan, the market delivers. (Zeegers, 2014). Especially for infrastructure, the integrated model is popular and covers a large part, maybe more than half of the projects tendered. It is understandable because of the nature of infrastructural projects. Specifications for a road, for instance, a bridge, dyke, or a highway are maybe easier to define than for instance a museum or a town hall. But also these kinds of buildings are more and more outsourced to the market in an integrated way including finance, maintenance, and operation. (DBFMO contracts). Even if it is extremely difficult for the client to define a project at the start, the choice is to outsource it all not based on weighing different arguments or pros and cons but because it is the policy of the government. During our course, we will showcase successful and failing cases of both delivery systems.